Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook

Certain foods and eating habits can cause a leaky gut, leading to a host of illnesses. In its new book, the Alliance for Natural Health International offers a blueprint of ways to heal your gut and immune system.

Certain foods and eating habits can cause a leaky gut, leading to a host of illnesses. In its new book, the Alliance for Natural Health International offers a blueprint of ways to heal your gut and immune system.

Our gastrointestinal tract is basically a pipe that runs from mouth to exit. It includes our esophagus, stomach, small and large intestine, rectum and digestive organs, the liver, gall bladder and pancreas. It’s meant to be a mostly sealed tube that has its own food factory and defense system, with friends and partners to make it all work seamlessly.

A healthy adult gut harbors a complex community of around 100 trillion microbial cells, referred to as the gut microbiome. That’s about 10 times the number of human cells we have in our bodies.

In return for a safe and comfortable home, our gut microbes are meant to help us digest our food and make nutrients (including folate, vitamin B12 and short-chain fatty acids) and other cofactors to see us through a vital, happy, healthy life.

Nutritional science is helping us to realize that food is fundamentally a form of information for the body. A single, healthy meal with a bountiful supply of plant foods may contain many thousands of discrete naturally occurring compounds that do a lot more than just provide energy to fuel the body.

These gut microorganisms use plant compounds that we’ve consumed to regulate a wide range of critical functions (transcriptomics) including our appetites, our immune systems, our brain function and the way we store and use energy.

Many of these bioactive compounds in our food act as signals that help regulate metabolic pathways. Very importantly, the quality of our diet affects the way in which our genes are expressed through epigenetic processes such as DNA methylation and histone modification that turn on or off particular genes, or for that matter, make some whisper or shout loudly.1

The whole community project is policed by the gut’s immune system that resides in the walls of the tube (the mucosa). But like any community, when the fabric of social society breaks down, problems start occurring.

In the case of the gut, this happens when our partners and friends don’t receive the right nourishment or conditions, when the gut stays inflamed for long periods, when the mucosa loses its ability to distinguish friend from foe, or self from non-self, when the good guys turn to bad guys or when the gut starts to ‘leak’ its contents in the body cavity.

If you can’t get things back under control, mayhem and disease become the order of the day.

Your immune control center

The gut mucosa is comprised of three main parts. The outermost layer is the nonhuman microbiota layer. Next is the highly specialized, ‘intelligent’ mucous layer (or layers in the case of the colon) that separate the gut contents from the innermost layer of cells of our gut, the intestinal epithelium. The gut epithelium is one of the most biologically active areas of the body.

These cells replace themselves more often than any other part of the body. Each epithelial cell might be replaced every two to five days. Compare that against an average of 15 years for a muscle cell.2

This epithelial area is loaded with different types of immune cells that make up a veritable army to handle organisms that we, and our commensal microbes, consider to be bad for business. Examples include dendritic cells, macrophages, lymphocytes and T regulatory cells.

If your immune system is in balance with your gut microbiota, you are the proud owner of the most sophisticated system of medicine known to our species. It’s estimated that over 70 percent of all our immune activity goes on in our gut.

When the system is over-taxed, or when the function of the gut mucosa starts to break down or you start to experience leaky gut, the system we take for granted on a daily basis falls apart.

When your gut mimics a teabag

Certain foods often damage or make our gut wall penetrable or even trigger intolerance or sensitivity, contributing to leaky gut syndrome, much like water through a teabag. For most people, this decline to a leaky gut is gradual over many years. Initial symptoms like mild indigestion, bloating and gas are waved off as normal until something more acute ensues, often years later.

Some symptoms that your body might give you as a red flag include digestive disruption, chronic fatigue, ulcers, arthritis or joint pain, headaches, poor immune function, mood swings, depression or anxiety, memory loss, confusion, hormone imbalances and unexplained weight fluctuations.

The length and breadth of that list should give you an inkling of how important our gut function is to us and more specifically why we need to be a good host to our microbial partners.

But the good news is you can help rebuild the integrity of your gut—especially by altering what, how and when you eat, something that’s largely within your control.

Gut-brain cross talk

Basic anatomy tells us that the gut and the brain are connected via the vagus nerve. It’s a principal component of the parasympathetic (‘rest and digest’) nervous system, the side that’s not under our conscious control (autonomic nervous system).

Apart from being the longest nerve in the autonomic nervous system, the vagus nerve helps to regulate heart rate, blood pressure, sweating, digestion and even speaking to a certain extent because it controls the muscles of the voice box.

It runs all the way from the brain stem to the stomach and intestines and supplies nerve function to the heart, major blood vessels, lungs, airways and the esophagus. It’s hugely important in our lives, and sudden overstimulation can drop blood pressure, slowing the heart and causing a loss of consciousness.

It’s also a two-way street that conveys information back from these organs to the brain. This brain-gut axis not only involves the nervous system, but also the endocrine and immune systems—and the gut microbiota.

Interestingly, cutting the vagus nerve doesn’t affect digestive function, suggesting that our gut has a ‘mind’ of its own. Our brain may have 100 billion neurons, but our gut has 100 million, further suggesting that it really is our second brain.

There’s no coincidence in the fact that our microbiota, in residence within our second brain, are responsible for the digestion of foods, the creation of hormones and vitamins, response to medicine and infections, detoxification, control of blood sugar and cholesterol levels and determining the risk of developing certain chronic and autoimmune diseases.

Our gut microbes are involved in just about every process in the body, including defense. Our health is deeply dependent on the diversity and vitality of our internal ‘rainforest.’ What happens in our gut influences how we feel, how we think, how we behave, how we defend ourselves and how we function.

Eat a rainbow everyday

Consume foods that represent all six color groups of the ‘phytonutient spectrum’ each and every day!

Yellow foods

Apples, banana, bell peppers (yellow), corn, chickpeas, ginger root, lemon, millet, pineapple, popcorn

Benefits: Cancer protective, healthy inflammatory response, cell protection, cognition, skin health, eye health, heart/vascular health

Red foods

Apples (red), beans (adzuki, kidney, red), beets, bell peppers (red), blood oranges, cranberries, cherries, goji berries, grapefruit (pink), grapes (red), plums (red), pomegranate, potatoes (red skin), radicchio, radishes, raspberries, red leaf lettuce, red onions, strawberries, sweet red peppers, rhubarb, rooibos tea, tomato, watermelon

Benefits: Cancer protective, healthy inflammatory response, cell protection, gastrointestinal health, heart health, hormone balance, liver health

Green foods

Apples (green), artichoke, asparagus, avocado, bamboo shoots, beans, bean sprouts, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, celery, cucumbers, edamame (soybeans), green tea, “greens” (arugula, beet leaves, chard, dandelion leaves, kale, lettuce, mustard leaves, spinach, etc.), lettuce, limes, okra, olives (green), pak choy, peas,rosemary, spinach, watercress

Benefits: Healthy inflammatory response, brain health, cell protection, skin health, hormone balance, heart health, liver health

Orange foods

Apricots, bell peppers (orange), carrots, grapefruit, mango, nectarine, orange, papaya, pumpkin, squash (butternut/acorn/winter), sweet potato, tangerines, turmeric, yams

Benefits: Cancer protective, immune health, cell protection, reduced all-cause mortality, reproductive health, skin health, source of pro-vitamin A

Blue/Purple/Black foods

Blueberries, blackberries, cabbage (purple), carrots (purple), cauliflower (purple), eggplant, figs, grapes (purple), kale (purple), olives (black), plums, potatoes (purple), prunes, raisins,

rice (black/purple)

Benefits: Cancer protective, healthy inflammatory response, cell protection, cognitive health, heart health, liver health

White/Tan/Brown foods

Apples, beans (butter, cannellini, etc.), cauliflower, cinnamon, clove, coconut, cocoa, coffee, dark chocolate, flaxseed, garlic, ginger, legumes (chickpeas, dried beans, lentils, peanuts, etc.), mushrooms, nuts (almonds, cashews, macadamias, pecans, walnuts), onions, pears, seeds (flax, hemp, pumpkin, sesame, sunflower, etc.), shallots, tea (black, white), whole grains (amaranth, buckwheat, corn, millet, montina, oats, quinoa, rice, sorghum, teff—all naturally free of gluten)

Benefits: Cancer protective, antimicrobial, cell protection, gastrointestinal health, heart health,liver health, hormone balance

Read on for more common triggers of gut and immune dysfunction and tips for how to heal them.

The biggest gut killers

A healthy, robust gut can manage a certain number of foods containing so-called “antinutrients.” Depending on your cultural background, ethnicity and the foods you’ve become used to, you may not experience any adverse effects at all. But if you have a sensitive gut, autoimmune disease in your family history, or other health or fatigue issues, try to avoid overloading your body with the following antinutrients.

Saponins

Vegetables and grains that cause a foam on the water as you cook them (onions, rice, potatoes, soy beans, legumes) contain saponins, which can take out whole sections of your epithelial layer.3

Rinsing rice and soaking legumes (pulses and beans) overnight before cooking them rids them of most of the saponins—cooking legumes for over six hours can destroy the lectins, too, and you can speed this up if you have a pressure cooker. The reason why we have historically cooked onions on a low heat until they become transparent (before adding the other ingredients) is to ensure that the saponins are destroyed.

Gluten

The tight junctions in the lining of your gut mucosa have doorways acting as regulators between the internal environment in the gut and the body. Vital food nutrients pass across the intestinal wall, toxins are kept out, but the doorways are only flung open when the gut’s defense system meets a pathogen that’s too fierce for it to cope with alone.

By opening the tight junctions, and therefore making the gut permeable (leaky), the body’s full immune armory can be brought to bear. A protein molecule called zonulin is the gatekeeper, opening and closing the doorways when necessary.

All of this has worked well up until we were faced with gluten and diets that make our guts inflamed. Gluten is actually not just one compound. It’s a mixture of hundreds of distinct proteins that are common to cereal grains such as wheat, barley and rye.4 They can be loosely divided into two classes of protein: gliadin that helps bread to rise when it’s baked, and glutenin that gives bread its much-loved elasticity.

In a nutshell, gluten mimics the action of zonulin and flings open the doorways of the gut mucosa, thereby creating a leaky ‘teabag’ gut. Apart from the gut contents flowing out into the body, so too do our intestinal microbes—whether they be good guys or bad guys—in search of new homes in our organs or worse, our brain.5

Both actions have consequences that cause the big guns of the body’s immune system to crack down hard, causing inflammation, which underlies all major chronic diseases, from most forms of cancer to heart disease, from arthritis to type 2 diabetes or obesity.

Even worse, the immune system can become confused and start attacking some of our own cellular proteins thinking that they’re enemies. Do this for a prolonged period of time and you have the ‘perfect storm’ that triggers autoimmune diseases, which are rising fast with over 100 now described in the medical literature.6

10 ways to feed a healthy gut

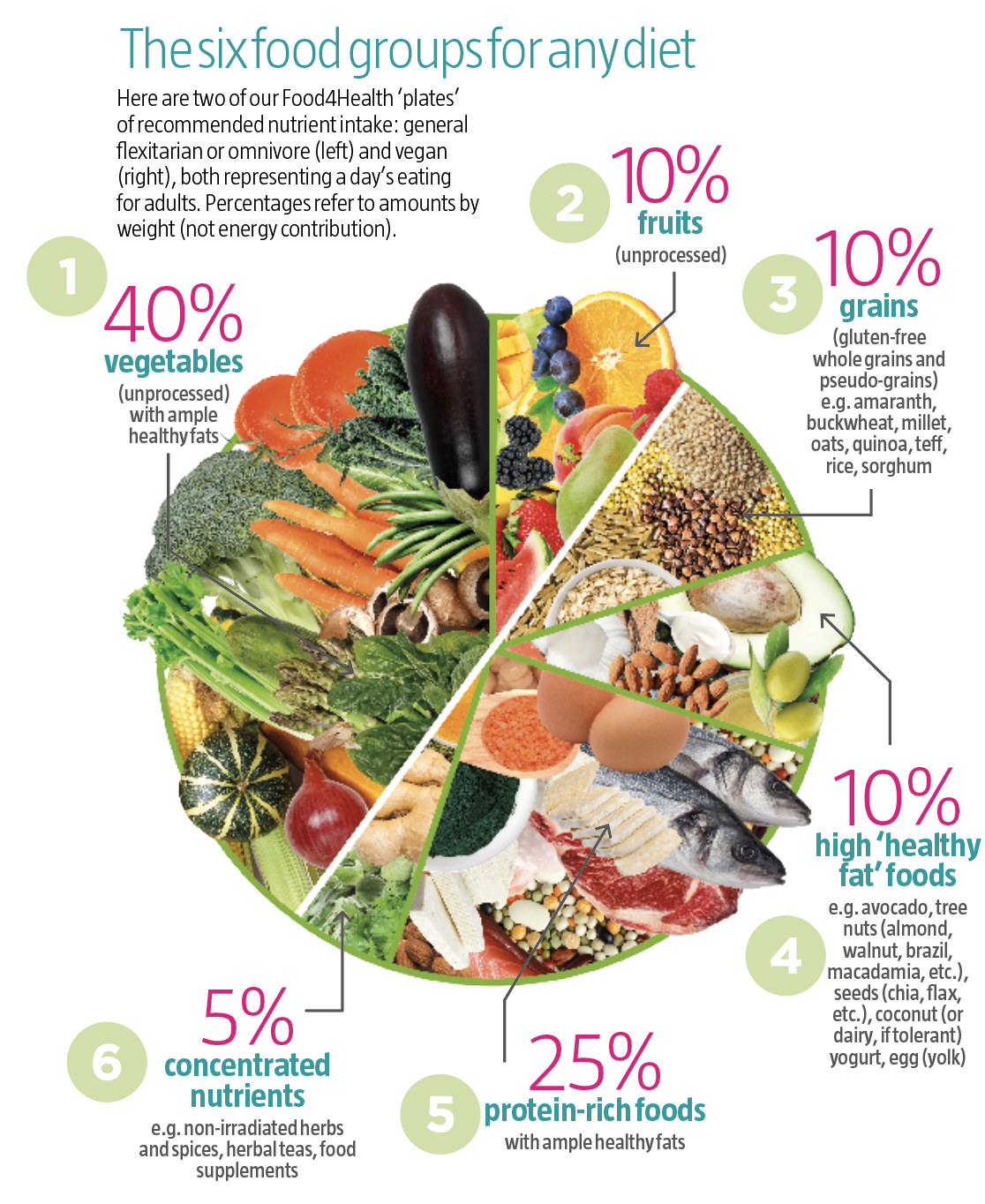

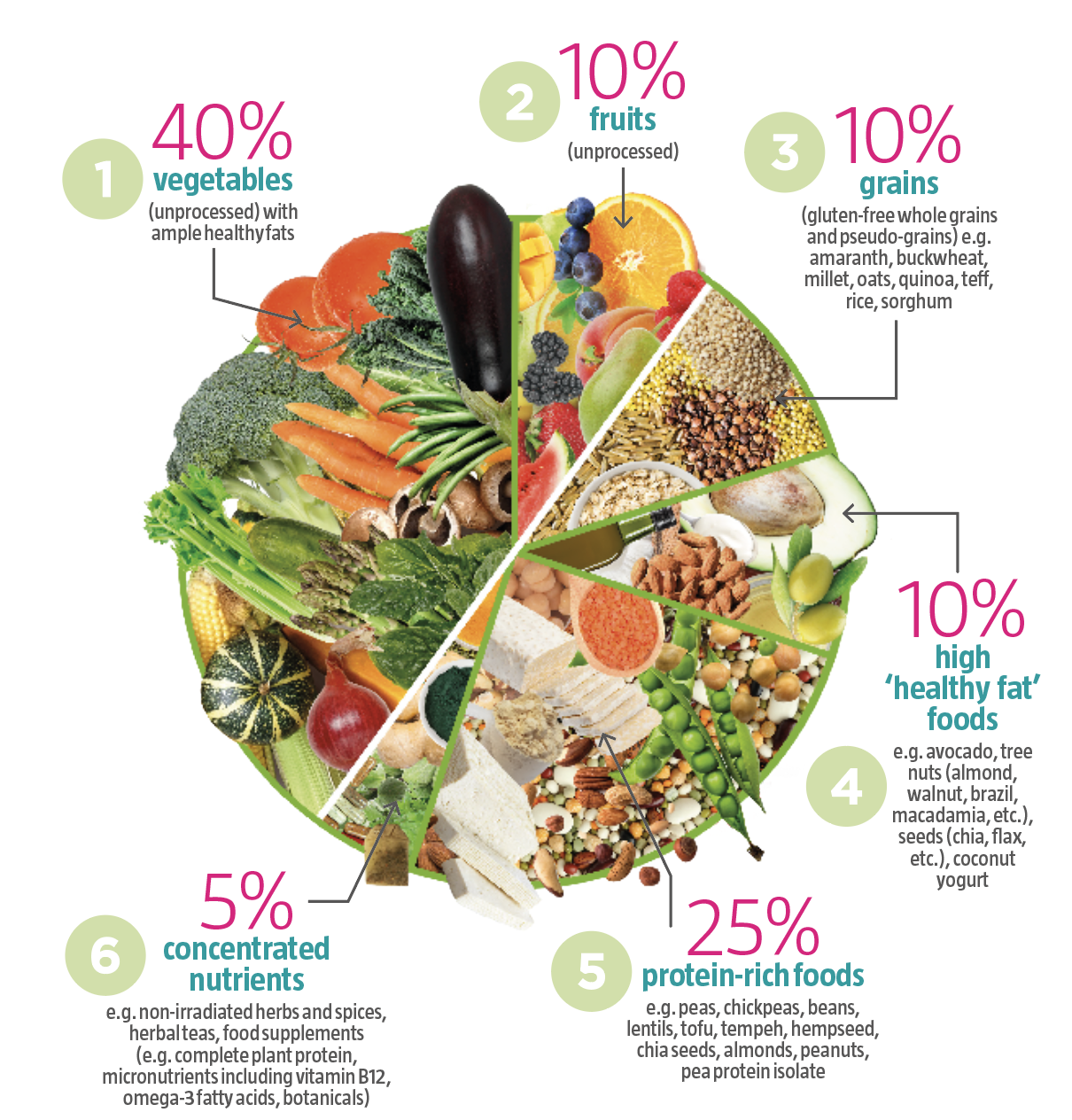

1) Macronutrient contribution by energy (kcal or kJ) should be approximately 20 percent protein (4 kcal/g), 25 percent carbohydrates (4 kcal/g) and 55 percent fats (9 kcal/g) (see page 34 for more on the Food4Health “daily plate” recommendations)

2) Minimize consumption of highly processed foods and avoid all refined carbohydrates

3) Consume plenty of fresh, raw or lightly cooked plant foods (in a roughly 4:1 ratio of vegetables and fruit) that include all six color groups each day (green, red, yellow, orange, blue/black/purple, white/tan/brown)

4) Avoid high-temperature cooking methods (frying, grilling, BBQ) unless brief. Minimize heat damage to proteins, fats, starches and other carbs by using slow cooking methods

5) Healthy fats for cooking include virgin coconut oil, unfiltered extra virgin olive oil, virgin avocado oil, safflower oil, and butter or ghee (the latter two only if no lactose intolerance). Other healthy fats for addition to other foods include oils of flaxseed, hempseed and macadamia.

6) Consume plenty of fresh herbs and non-irradiated, preferably organic spices, along with herbal teas (made with real herbs/spices rather than flavorings)

7) Avoid snacking and try to maintain five or more hours between meals

8) Consume at least 1.5 liters of spring or filtered water daily between meals (more if exercising intensively)

9) Avoid all foods that trigger sensitivity, intolerance or allergy

10) Seek advice from a qualified and experienced nutritional health professional on the most appropriate concentrated sources of nutrients, herbal teas and/or supplements (concentrated sources of nutrients).

Milk

Milk contains a naturally powerful opiate from the morphine family. Casomorphins are peptides (protein fragments) released from the digestion of the protein casein found in milk. They are opioids and can have an addictive effect, mimicking the effects of drugs like heroin and morphine.

Once the incompletely digested peptides are absorbed into the body, they bind to opiate receptors in the brain and have the power to alter behavior and physiological reactions.7

Mother’s milk is definitely a food of the gods for babies, and even the opioid components serve a purpose. Not only do the casomorphins slow intestinal movements and have an anti-diarrheal effect, but they also calm the baby and assist the bonding process with the mother. That’s one of the reasons why babies sleep so peacefully and soundly after they’ve breastfed.

An infant’s gut also produces lactase, the enzyme needed to break down lactose (milk sugar). But lactase production drops off steeply after weaning, making lactose intolerance the most common and well-studied food intolerance in the world. It’s also virtually incurable without the aid of external lactase enzymes.

Despite the range of nutritional factors in mammalian milk, there are still a very significant number of people, up to 100 percent in some ethnic groups, for whom milk represents a significant health risk rather than a superfood. While raw milk—preferably raw A2 milk—is unquestionably the healthiest and best-tolerated cow’s milk option, it still doesn’t eliminate issues of lactose intolerance, milk protein intolerance or the link to autoimmune conditions that affect some subsets of the population.8

Secondary lactose intolerance, caused by impaired digestion through an imbalanced gut microbiome that affects the ability to make lactase, can also happen at any time in life.

Consumption of cow’s milk, alongside gluten, also leads to one of the highest levels of intolerance due to the similarity in structure between some of the proteins produced by in the human body.

Unless you have a rock solid, healthy and impermeable gut, which is extremely rare given the prevalence of leaky gut caused by today’s high dependence on gluten and wheat-based foods, some of the milk protein fractions will leak out into the surrounding tissues.

Once outside of the gut, they may trigger an immune reaction as the body reacts to the foreign proteins and starts destroying them. It’s a perfectly natural process for your immune cells to then create a ‘memory,’ which will ensure a faster reaction the next time the same trigger occurs.

Patients with type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, multiple sclerosis and latent autoimmune diabetes in adults have been found to have significantly increased levels of antibodies to different milk fractions in research studies.9

Lectins

In order to survive, plants have evolved an arsenal of chemical warfare agents as part of their survival strategy. Plant lectins are one of the prime agents in that arsenal, although they’re thought to have other functions in a plant too, especially ones linked to cell communication and recognition.

It was only around 12,000 years ago that grains and beans (legumes) became common staples. Before that time, we had no way of eating these plants in quantity as we didn’t cultivate food crops or process them into edible foods. As a result, our genome and our gut microbiome can be challenged by these ‘new’ lectins—especially when they assault our system in quantity.

Plant lectins represent a very diverse family of protein molecules. One of their stand-out roles is protection against invading microbes and insects. They’re referred to as ‘sticky’ proteins because they bind to particular sugar molecules on cell membranes, especially ones called glycoproteins and glycolipids.10

Most plant lectins cause cells to clump together, and once attached to sugar molecules, they can become stealth invaders. They can hack into a microbe or insect’s system and really mess with it.

Take for example, sialic acids. These are sugar molecules involved in cell-to-cell communication. When lectins bind to sialic acid, they’re able to hack in and disrupt the communication between neurons. In this way, they can paralyze an insect, then release pheromones that call in the insect’s predator to do away with them as they lie there paralyzed.11

Lectins are produced by all classes of living organisms and even by different types of cells. They are structurally very diverse and can have highly specific functions like enzymes or antibodies. Some foods are naturally higher in lectins than others, while particular lectins are more toxic than others.

For instance, improperly cooked kidney beans can kill you, as can a few molecules of ricin—the lectin from the caster bean plant. Luckily, this is one time that size really does matter. The dose that paralyzes an insect may not be enough to do us any harm at all, if we’ve got a robust constitution. Or it may take many years of regular, low-level exposure before we feel the effects.

Our sensitivity to lectins varies. Peanuts famously have lectins that are very problematic for many. And if you’ve ever felt bloated, gassy or tender in the gut after indulging in too many edamame, it may have been down to lectin sensitivity.

One of the first lessons we learn about cooking dried legumes, especially red kidney beans that are loaded with the lectin phytohemagglutinin, is that they need to be soaked and boiled before they’re safe to eat.

The same goes with the soybeans in edamame. They haven’t been cooked long enough to lower the lectin levels. Typical symptoms of lectin sensitivity include bloating, diarrhea, nausea and gas, all of which can lead to a leaky gut barrier over time and exposure.

California-based physician Steven Gundry, one of the foremost clinicians and researchers into lectins and author of The Plant Paradox: The Hidden Dangers in “Healthy” Foods that Cause Disease and Weight Gain (Harper Wave, 2017), argues that we have only been exposed to lectins from the Americas, such as those in tomatoes, for a mere 500 years. This, he maintains, along with exposure to too many grains and legumes, is one of the drivers of the epidemic of autoimmune diseases.

It’s now thought that sensitivity to wheat germ agglutinin, the lectin in wheat, is another contributing factor to the rise in non-celiac gluten sensitivity. The adverse reactions to wheat from which many suffer might not solely be down to the action of gluten on our tight junctions.12

The good news is that, addressed early enough, it’s all reversible. In fact, Dr Gundry has been so successful in changing the health fortunes of his patients with a lectin-free diet—many of them vegans and vegetarians—that he’s no longer a surgeon, preferring instead to use food and lifestyle modification as a healing modality.

Phytates

Phytate or phytic acid, concentrations of which are highest in plant seeds, bran, grains, nuts, beans and other legumes, often gets a bad rap. However, like everything in nature, it’s there for a reason.

Phytic acid, also known as inositol hexaphosphate or IP6, provides the body with an important source of phosphorus as well as the natural sugar alcohol inositol that helps support neurotransmitter function in the brain as well as the binding of some steroid hormones at their receptor sites.

Its bad press comes from the fact that it has a strong ability to bind to and reduce the absorption of minerals in the gut, especially zinc, iron and calcium. That’s how it’s attracted the label ‘antinutrient.’3

Anyone who is consuming large amounts of phytic acid-rich foods on a regular basis should be aware of its potential effects, especially on the absorption of zinc (relevant to both women and men) and iron (especially for women, who require iron in greater quantities especially before menopause).

In nutritional status surveys in both industrialized and developing countries, circulating zinc levels in the blood are often found to be low, with around half the world’s population considered to be deficient.13

This is a major issue given zinc’s crucial role in balancing the adaptive side of our immune system. It’s also worth noting that zinc excess has many of the same downsides as zinc deficiency in terms of how it modulates the immune system.

Therefore, trying to get the level of zinc right in the body is something of a fine art as well as a science. Most zinc now consumed in the West is not from foods traditionally rich in zinc such as grass-fed cattle or wild fish, but rather in fortified breakfast cereals or in one-a-day supplements taken alongside phytate-rich breakfast cereals or bread. This impacts zinc and iron absorption.

Cooking phytic-acid rich foods, such as legumes, sprouting seeds and fermented foods (e.g. sourdoughs) significantly reduces phytic acid concentrations. Consuming supplements containing zinc away from phytic-acid rich foods is another important way of ensuring the amount of zinc in your bloodstream is optimal.

Be leery of lectins

For those of you who are, or think you might be, sensitive to lectins, the biggest offenders include:

• grains

• legumes (including peanuts)

• seeds (including cashews)

• some of the much-loved members of the deadly nightshade family—tomatoes, eggplants, peppers, potatoes, even goji berries.

Rid yourself of lectins through long cooking times or by using a pressure cooker, which kills lectins but preserves most nutrients.

With legumes, think long cooking times, just like a traditional dahl. A true dahl is often slow cooked for several hours, substantially reducing the lectin content.It takes time (up to about 6 hours) at a gentle boil to destroy these audacious chemical weapons.

Opt instead for low-lectin vegetables including avocados,

leafy greens, the entire cruciferous family (broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, pak choy, kale, etc.), carrots, cooked sweet potatoes, asparagus and all berries.

Make sure any soy products you eat are properly fermented, and check out companies catering to the needs of vegans with lectin-free products.

Another strategy is to pair lectin-containing foods with foods that eliminate lectins. In India, for example, it’s common to eat a lot of okra alongside lentil-based dhal. The mucilaginous part of okra is particularly good at binding lectins, as is seaweed, especially bladderwrack.

It also helps to peel and deseed fruits and vegetables. Many lectins are found in the skins and seeds.

If you’re a bread lover and can tolerate gluten, opt for a traditionally fermented sourdough and let those clever microbes lower the level of both the gluten and the lectins. Please note: many supermarket sourdoughs are not authentic.

Oxalates

Oxalates are abundant in many plant foods, especially spinach, rhubarb, nuts (and nut butters) and—wait for it—French fries and potato chips. Therefore, vegans and vegetarians are often found to be more susceptible to high oxalate, which contributes to a high risk of forming the most common type of kidney stones (calcium oxalate stones, as opposed to uric acid stones, which are commonly associated with gout).14

You can readily be tested for oxalate in a blood test. If you have a tendency toward forming calcium oxalate stones, you’ll benefit from eating fewer high-oxalate foods and more foods rich in calcium (such as leafy greens, legumes and amaranth).

Despite the stones being created by calcium oxalate crystals, calcium in the diet actually binds the oxalate in the gut and reduces the amount that is pushed out via the kidney and into the urine. Make sure that you keep your magnesium intake up too, as magnesium has been found to inhibit calcium oxalate crystallization.

Histamine

Histamine intolerance is a condition in which, for one reason or another, the body produces too much histamine. That may be because the enzyme that naturally breaks down histamine produced in the body, diamine oxidase (DAO), doesn’t work as it should. This can be caused by many factors such as a leaky gut, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), inflammatory bowel disease or particular food or drug interactions.

Low-histamine diets, as with low-oxalate diets, are only relevant for those with specific health issues, in this case, histamine intolerance. One of the problems, however, is that histamine intolerance is often undiagnosed, and it may underlie common non-celiac adverse reactions to gluten-containing foods (such as non-celiac glutamine sensitivity).15

If this sounds like you, it’s advisable that you seek help from a nutrition professional, but also stay away from high-histamine foods such as alcohol, mature cheese, all fermented beverages, avocados, eggplant, spinach, canned and processed foods and dried fruits.

Excerpted from Reset Eating by Rob Verkerk PhD and Meleni Aldridge (Alliance for Natural Health International, 2020). Visit www.anhinternational.org to get your copy.

https://www.wddty.com/features/a-guide-to-good-gut-health/?utm_medium=email&utm_source=wddty&utm_content=Your+guide+to+better+gut+health&utm_campaign=FREE+MEMBERS+enews+%28A+guide+to+good+gut+health%29+-+01.04.2021

|

References |

|

|

1 |

Inflamm Res, 2021; 70: 29–49 |

|

2 |

Cell, 2005; 122: 133-43 |

|

3 |

Int J Nutr Food Sci, 2014; 3: 284–9 |

|

4 |

Nutrients, 2013; 5: 771–87 |

|

5 |

Nutrients, 2015; 7: 1565–76 |

|

6 |

Clin Rev Allergy Immunol, 2012; 42: 71–8 |

|

7 |

J Food Biochem, 2019; 43: e12629 |

|

8 |

Hum Biol, 1997; 69: 605–28 |

|

9 |

Horm Metab Res, 2002; 34: 455–9, J Immunol, 2004; 172: 661–8 |

|

10 |

Int J Mol Sci, 2017; 18: 1242 |

|

11 |

FASEB J, 2015; 29: 3040–53 |

|

12 |

Tox Appl Pharmacol, 2009; 237: 146–53 |

|

13 |

Nutr Rev, 2018; 76: 793–804 |

|

14 |

Arch Ital Urol Androl, 2015; 87: 105–20 |

|

15 |

Inflamm Res, 2018; 67: 279–84 |